Making Drugs Good Enough

Value chains in Pharmaceuticals, and the CAR T-Cell Therapy Market

Feedback welcome on Twitter @caseloadblog.

I’ve been brushing up on my Clayton Christensen this week, and as always, his ideas have sparked some interesting thoughts. In The Innovator’s Solution, Christensen describes a pattern in value chains that determines when vertically integrated companies succeed, compared to modular value chains:

When the product is not good enough to satisfy the needs of a given customer, an integrated or interdependent solution will win out, because it places the fewest constraints on the engineer and product designer. That is, the engineers and designers can craft all of the steps that go into creating the product exactly as needed, because they control all of those steps.

When the product IS good enough to satisfy the needs to a given customer, the integrated company actually loses out to a modular value network. In a modular value network, standardized interfaces emerge such that the inputs to each step can be created by any firm. This standardization allows for many suppliers to compete, which increases the speed and variety with which end customers can be served. Since the resulting product is ‘good enough,’ the performance constraints that arise from standardization don’t matter nearly as much as speed and variety.

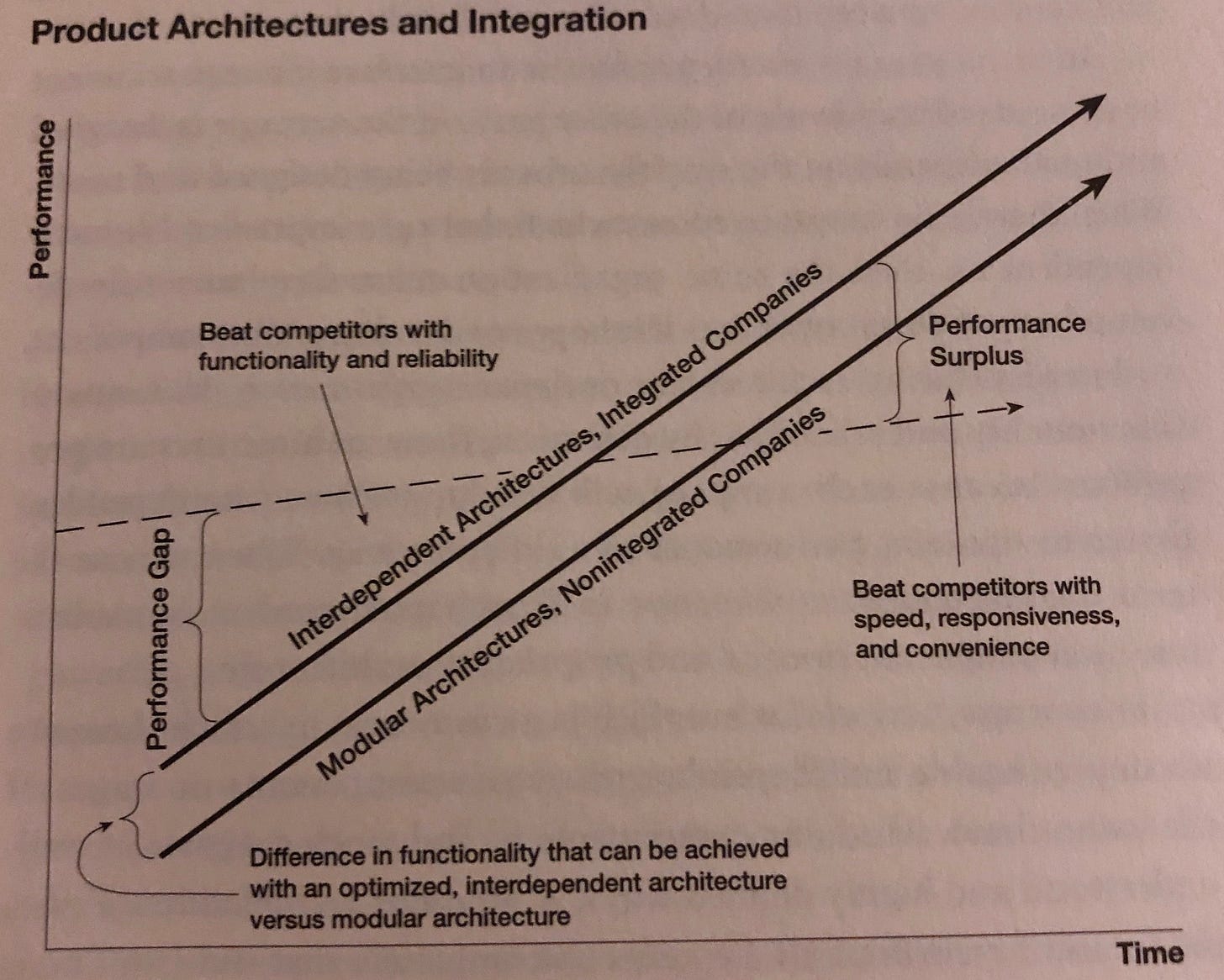

The Famous Chart: The dotted line represents ‘good enough,’ i.e. the performance required to satisfy a customer in the market. Graphic from The Innovator’s Solution, Chapter 5.

Which drugs are good enough?

In this context, it’s striking that in some therapeutic areas, existing drugs are well above the line of ‘good enough’, while in others, the state of the art is well below the line.

‘Good enough’ therapies might include antibiotics for common infections: assuming the drug cures your infection, you are satisfied. Improved efficacy might still be possible in the form of lower doses, fewer side effects, or faster results, but there is a limit to how much extra money most patients would be willing to pay for these things.

‘Not Good Enough’ therapies might be cancer drugs—there are no drugs (yet!) that offer a permanent and assured cure. Furthermore, the need for these types of drugs is extremely urgent for consumers: the cost of not getting the very best therapy could very well be death. In that sense, the performance of a therapy required to satisfy a given patient is extremely high. And patients are willing to pay quite a bit more for a therapy that is even a tiny bit better than the alternative.

Of course there are also ‘not good enough’ therapies that treat less urgent conditions - I have seasonal respiratory allergies, for example, which aren’t life-or-death, but there are no drugs that are quite good enough to relieve them.

Returning to Christensen for a moment, we might expect the value chain for the ‘good enough’ drugs to be modular, and to differ significantly from the value chain for ‘not good enough.’ Is that the case?

The modularity of the drug market

I would argue that the value chains are different, but to a limited extent: the drug landscape is fundamentally modular. That is, when a physician makes a diagnosis and develops a treatment plan for a patient, they generally are choosing from a menu of available (FDA-approved) drugs. Those drugs are easily compared among a fairly standard set of patient outcomes, which include the side effect profile, the efficacies observed in clinical trials, etc. As an example, a doctor might want to prescribe a statin for a patient with heart disease, and the available options can all be ranked by their observed LDL reduction.

Furthermore, once the doctor makes a decision, the drugs are delivered to the patient via a standard distribution channel, the retail pharmacy. The specific statin, doctor, and pharmacy are all interchangeable to a high degree, which is exactly what we mean by modularity. And it’s a system that’s fast and flexible; patients get the right drug for their situation, and they get it quickly.

There is one point of vertical integration in the branded drug supply chain, which is between the design/R&D, the manufacture, and the marketing of the drugs. ‘Big Pharma’ companies broadly encapsulate all three functions, which combined with the modularity downstream, has led to outsized profits.

Tight interdependence on the cutting edge

Christensen’s framework would predict increased integration for therapy areas that are ‘not good enough,’ and I would argue that that’s correct. Indeed, some of that latest cancer treatments (such as CAR T-Cell Therapies) incorporate such an integration. Here is a description of Kymriah (a CAR T-Cell drug made by Novartis) from page 24 of its prescribing information.

Since KYMRIAH is made from your own white blood cells, your healthcare provider has to take some of your blood. This is called “leukapheresis.” It takes 3 to 6 hours and may need to be repeated. A tube (intravenous catheter) will be placed in your vein to collect your blood. Your blood cells are frozen and sent to the manufacturing site to make KYMRIAH. It takes about 3-4 weeks from the time your cells are received at the manufacturing site and shipped back to your health care provider, but the time may vary.

Technical language aside, the important part here is the extremely tight link between the patient and the drug company: the patient’s cells are shipped to the drug company, who processes those very cells into a drug, which is then shipped back to the cancer center for infusion into the patient. (Your humble correspondent finds it absolutely miraculous that this works.) Christensen would recognize this dynamic as interdependence: the drug itself is literally extracted from the patient by the HCP, then shipped to the manufacturer for processing, and shipped back to the HCP for infusion.

That interdependence comes at cost: at least on of those costs is the massive constraint it places on distribution. As of this writing, there are only about 100 places in the country where Kymriah is available. Novartis simply cannot coordinate with much more while maintaining quality (or it will require a huge investment to do so, which may well emerge if the drug is successful). However, the interdependence is required to make the drug work, and because there is no ‘good enough’ alternative, the system will bear those high distribution costs even if Novartis does not. A patient who needs Kymriah will do what it takes to be at one of those 100 locations.

Furthermore, there is a modular equivalent of the same drug under development, as explained by Dana Farber Cancer Institute:

…researchers are developing a new generation of CAR T-cell therapies known as allogeneic or “off-the-shelf.” In this case, the immune cells are drawn from healthy donors and processed similarly in labs, but then frozen and banked so they can be quickly administered to a cancer patient.

[…]

There are, however, some concerns specific to this allogeneic approach that are being studied. The donor’s immune cells, while bearing CAR-targeting molecules might also recognize the patient’s normal tissues as foreign, creating a risk of graft-versus-host disease, says Nikiforow. Another uncertainty is how long the donor CAR T cells will persist in the patient’s body, since they might be actively rejected by the patient’s immune system.

The modular/allogeneic solution would absolutely bring down the costs and allow broader distribution. The question is, when/will CAR T-Cell therapy become ‘good enough?’ to enable that?

Let’s consider the case where the modular therapy emerges and is effective. This will serve to commoditize the providers, since the same therapy becomes available anywhere, and not just at one of the 100 existing centers. Incremental profits therefore shift to the manufacturer of that allogeneic therapy, who should now feel a keen incentive to pursue such formulations.

As an alternative case, perhaps the modular therapy does not emerge, but more autologous (i.e. relying on the specific patient’s cells, similar to Kymriah) therapies launch. In that case, it’s the drugs that become commoditized, and the providers that benefit, especially those providers that can support many of these drugs. If providers can combine these drugs with other non-drug treatments (like surgery), they become the point of integration in the value chain, and begin to capture far more of the profit.