Let’s talk care coordination. Recently in the space:

Accolade went public, then bought 2nd.MD

Quantum, an Accolade competitor, recapitalized

Ground Rounds, another competitor, raised money

Since Accolade is the public example, I’ll focus on them. (Disclosure, I work for Comcast, which invests in Accolade. More in footnote [1])

In this issue:

The Problem that Accolade Solves

The 2nd.MD Acquisition

Platforms for Point Solutions

Care Coordination Outlook

The Problem that Accolade Solves

Employers pay too much for health insurance and everyone knows it. There are probably lots of reasons for that, but lets start with a familiar culprit: the fee-for-service payment model [2].

Fee-for-service rewards providers, because it lets them use an information advantage to earn more. Doctors have expertise that patients don’t, so can recommend, and bill for, extra care. Patients don’t try to stop this, because they’d rather have more care than less, just to be safe. Second—moral hazard!—someone else is paying.

That ‘someone else’ is often an employer, which sponsors the patient’s health plan. For such employers, there are few good options to control costs. Common approaches, like narrowing provider networks or requiring a prior auth for every bit of care, have drawbacks. (And employers are still paying too much).

What employers really need is for employees to help control medical costs: shopping around, comparing prices, declining extra procedures. Employees, who have pre-paid for care via insurance, have no desire or obligation to do any of this. It seems like an impasse…and this is the problem that Accolade addresses.

Accolade is a care coordinator (or ‘navigator,’ I use the terms interchangeably). Members that need help accessing care can call an 800 number to speak with an Accolade Health Assistant, who can answer questions and make recommendations. Health Assistants are not clinically trained, but team up with doctors and nurses on staff. Critically, they’re also enabled by a data/tech/CRM platform that helps ensure they make the right decisions.

For employers, Accolade solves the two money-wasting problems we outlined above:

Reducing information asymmetry. Accolade’s doctors and nurses can advise plan members on clinical issues without concern for whether the member chooses more or less care.

Reducing moral hazard. Accolade can make the case to members when care is expensive and not needed. It can also direct members to less costly options (like outpatient centers instead of hospitals) by default.

This only works if members call Accolade in the first place—none of the cost-saving magic can happen without engagement. Customer experience therefore matters a lot; Accolade needs repeat interactions and good word of mouth to fully realize their value proposition. Employers likewise want engagement, and will go to great lengths to raise awareness for Accolade.

By engaging members, Accolade can understand exactly what care is needed. Data on provider cost and quality—organized and processed in the proprietary CRM—can then help optimize the cost/benefit of care decisions. Accolade is essentially coaching employees to make informed decisions that are good for themselves, in a way that is also good for their employer.

That strikes me as slightly precarious for Accolade. The employer wants cheap care, the member wants top quality care, and Accolade needs to deliver both. They must favor the employer’s needs (to demonstrate savings and ultimately sell more contracts), while appearing to cater to the member’s needs (in order to maintain engagement and trust, which in turn is needed for cost savings). Does that equilibrium result in the members’ best interests? Probably, but it’s a little messy due to principal-agent-type issues.

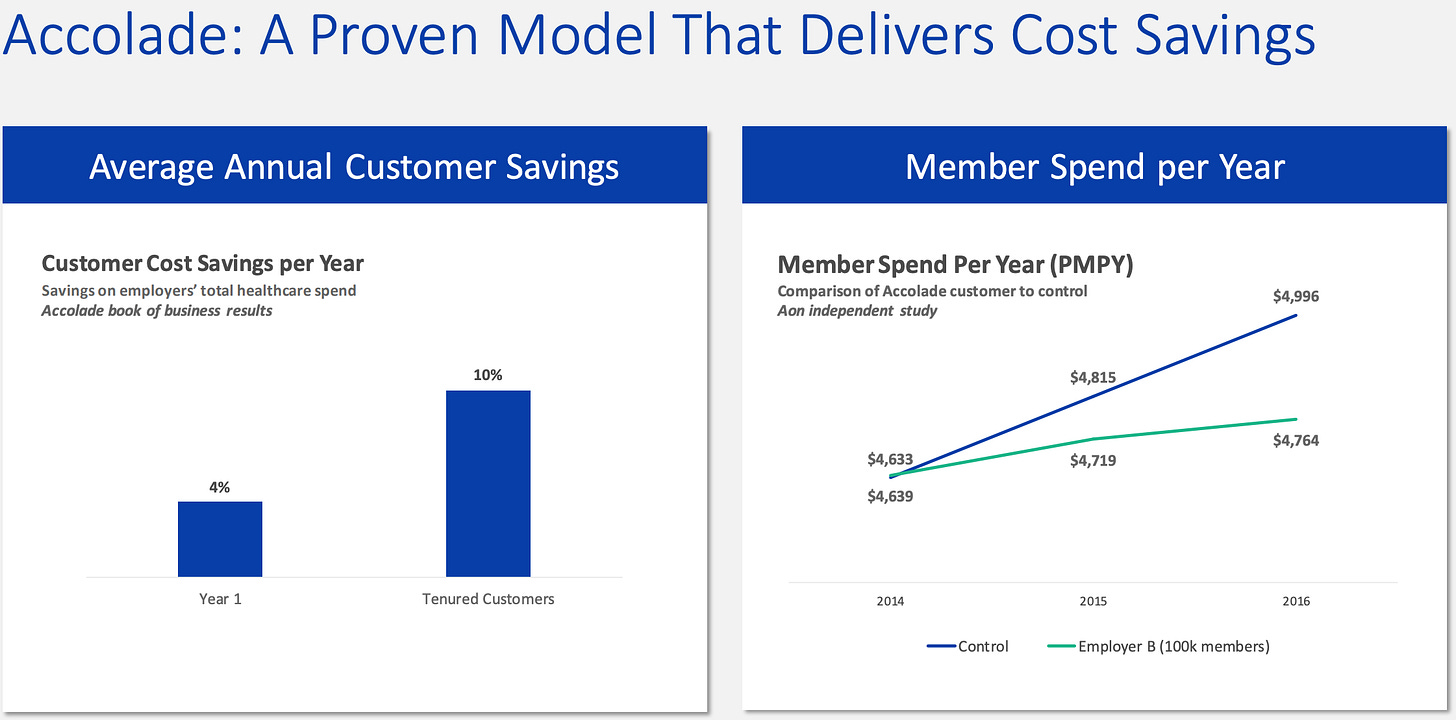

Which is not to say that Accolade shouldn’t be focused on employers’ costs: Employers hire them in order to save money overall, so Accolade’s value is roughly capped at the total amount of cost reduction they can produce, weighted by their clients’ belief in their ability to keep realizing those savings in the future.

It also means that Accolade’s best customers are those that (1) are under financial pressure to reduce their overall spend, but (2) also are willing to spend more right now on Accolade’s services. So, these employers are taking a risk by investing in Accolade, and I’d expect contracts to shift some of that risk back to Accolade by including a big incentive component.

On the other hand, the incentive component is a friction in the sales process because measuring the benefit is hard. There’s no perfect counterfactual against which to measure savings, so a model must be used. Models contain assumptions, and assumptions can be picked apart in contract disputes.

We began this section by lightly bashing FFS (who doesn’t love bashing FFS!?). I’ll end by noting that any savings Accolade creates for employers are losses for providers, mostly by limiting the inefficiencies in the FFS arrangement that providers are used to enjoying. On the margins, this should make providers more open to value-based care; a small accelerant of that trend. More on VBC later!

The 2nd.MD Acquisition

And but so Accolade paid a high multiple for 2nd.MD (13x revenue), which according to this fascinating page is closer to a pure software play (14x) than anything healthcare-related (0.5x - 6x). Why?

2nd.MD helps patients get second opinions on diagnoses and treatment plans. It connects patients with a curated network of clinical experts, and also connects the patients’ medical data to those same experts, who can then make an informed recommendation.

The quality of the physician network is important for confidence, because otherwise, patients could simply make another cheap telemedicine appointment with an undifferentiated doctor.

The data integrations ensure that the highly-qualified specialists get accurate inputs, and don’t spend expensive time tracking down the data themselves.

2nd.MD’s Big Numbers slide, if accurate, is genuinely impressive; when you’re saving $5k per interaction with almost perfect NPS, you’re probably on to something.

The slide also shows why Accolade is so interested:

If Accolade’s main goals, described above, are to create big savings and to drive high engagement, 2nd.MD convincingly checks those exact boxes.

High NPS is especially important because it translates directly into engagement: net promotors don’t just love the product, they also by definition tell their friends to go use it.

Accolade is competing directly with Grand Rounds, which already does the second opinion thing, so it’s become table stakes.

Strategic alignment + convincing numbers + competitive mandate = High Multiple

From 2nd.MD’s point of view, they are like Accolade in that they also need engagement to create the savings that justify their fees. However, to the extent that Accolade has solved for engagement, it is the de facto gatekeeper for companies like 2nd.MD—Accolade Health Assistants control referrals and recommendations. Accolade’s ownership of 2nd.MD therefore increases 2nd.MD’s value because Accolade is now incentivized to send patients to that service.

Platforms for Point Solutions

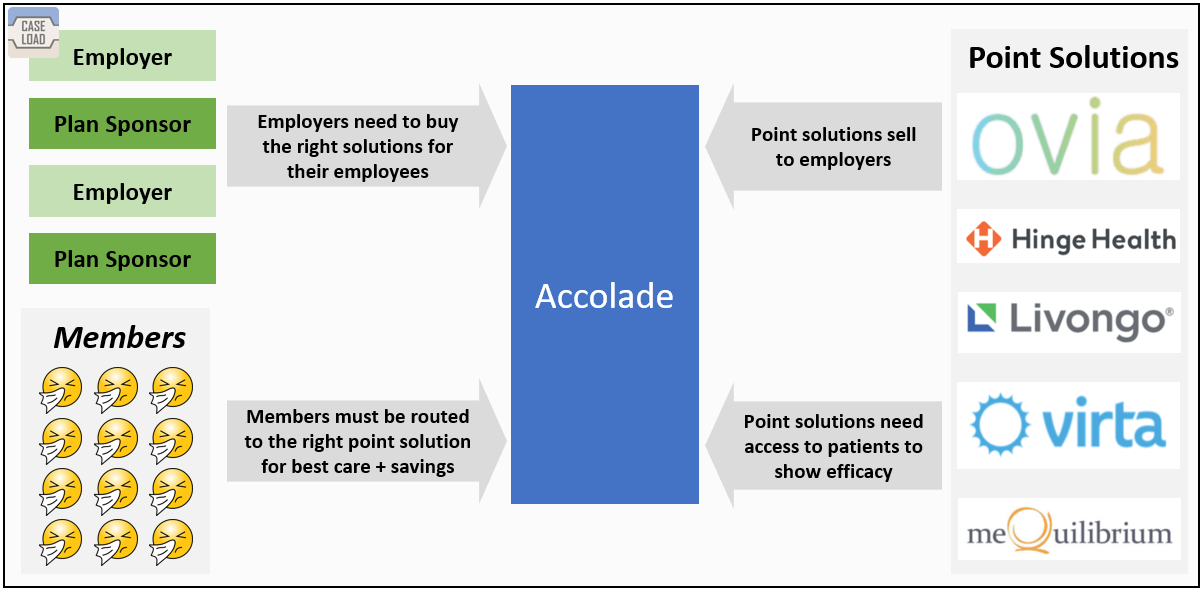

Interestingly, 2nd.MD is just one example of many health solutions that are competing to serve employees. Most such ‘point solutions’ address a given healthcare need—diabetes management, telemedicine appointments, etc. All of them need member engagement (notice a pattern?) to work, and a solution with no engagement is not getting a contract renewal.

Accolade has found a way to monetize its position as a key driver of patient volume to these point solutions, c.f. their Trusted Supplier Program, pitched thusly:

TSP customers give their employees more personalized health and benefits support, while significantly easing the burden facing their HR teams who want more streamlined benefits management. Accolade's TSP features a ten-step validation process to ensure each solution offered to employers is vetted and industry leading.

The TSP is a bundle of point solutions, vetted by Accolade, that Accolade’s customers can purchase. Three benefits:

Simplicity for buyers. Point solutions are complicated to buy and there are so many to asses that the decisions can overwhelm employers; Accolade’s bundle reduces the number of decisions that need to be made.

Cooperation. Plan members, and Accolade, are better off when employers purchases high-quality point solutions that are willing to share data and cooperate.

Access. Point solutions lucky enough to join the program gain priority access to more members, since Accolade will refer to the trusted supplier by default

Nevertheless, one line in the S-1, pg 122, gives me pause:

Customers pay Accolade on an incremental PMPM basis, and we generally receive a revenue share from the trusted supplier

Accolade, as the first point of contact for members, controls demand for all of the point solutions, and presumably can have a large impact on patient volumes for those services. They’re using that position to extract value from their suppliers, which is an Aggregator strategy—one that seeks to control the relationship between users and suppliers (clunky graphic below to illustrate).

That’s not a problem in and of itself, since aggregators tend to win by providing an excellent consumer experience. But unlike, say, Google, Accolade’s competition isn’t a click away—members don’t have any alternatives outside of the ones their employers buy for them.

Does Accolade bundle the best suppliers, or does it push the products of the highest bidders? Would benefits teams, who buy these services, always know the difference? It’s another principal-agent problem, and I wonder if competitors will follow, or if they’ll differentiate by foregoing the monetization, and pointing out that Accolade might not be positioned to impartially choose the best option for each employer.

Care Coordination Outlook

The final point about Accolade that I want to explore is its relationship to coordination and navigation services elsewhere in the healthcare system. A few examples:

Oscar (payer in the individual market): includes a concierge feature

Bright Health (payer in the Medicare Advantage market): Features Care Management Coordinators that actively manage members’ health to reduce costs to the plan

Iora: high-touch primary care that runs on capitated (i.e. value-based) contracts and includes many aspects of care coordination

From these examples, I’ll draw a quick heuristic: anyone that ultimately pays for care—plan sponsors, or risk bearing providers—can benefit when their patients make better decisions (or, more cynically, can benefit by nudging their patients). Care coordination provides that nudge.

And important implication is that as providers take on more risk (through value-based care initiatives), the payer becomes less invested in the savings that Accolade can generate; cost management becomes the provider’s problem. Care coordination, therefore, will integrate more naturally with the provider side than the payer side.

A second heuristic: higher cost patients require increased coordination. I think that’s why care coordination is so prevalent in the Medicare market (>88% of seniors have a chronic condition, many have multiple chronic conditions). The fact that Iora seems to be moving more into Medicare Advantage—which has higher concentrations of high-risk patients— strongly suggests that care coordination is in demand there.

Accolade seems to encourage this line of thinking in their S-1, filed under Growth Strategy (pg 119, my ephasis):

We see further opportunity to enter adjacent markets, including government-sponsored health plans, such as Medicare Advantage and Managed Medicaid…Our focus and experience in the navigation and coordination of benefits and healthcare, coupled with our technology investments, position us to take advantage of emerging healthcare trends surrounding care coordination and value-based care initiatives. We believe that we can leverage our existing platform and scalable solutions to successfully expand into these markets.

Accolade is aware of opportunity it’s current employer-sponsored market, but there’s a tension between committing to the still sizable opportunity there, and a timely entrance into the fast-developing Medicare Advantage market, where their existing approach might need to be heavily modified.

Let’s end with some food for thought: if care coordination is to become an essential part of any risk-bearing healthcare venture going forward, it makes sense to structure a care coordination firm not as an Aggregator—which intermediates patients and providers—but rather as a platform, which connects patients to providers. Currently, the Medicare Advantage startups are building their own coordination tools that integrate directly with their insurance function, but if they were all able to buy an Accolade product, it would enable a far larger number of plans to compete (because no one needs to make the technology investments, for example, that go into a coordination platform).

Just this week, Oscar has agreed to license their tech platform—which enables care coordination—to a payer-provider in Florida. I’m bullish.

Footnotes

[1] Disclosure: My employer, Comcast, owns about 5% of Accolade, and is also Accolade’s largest customer, per their S-1. However, I have no access to any nonpublic information about Accolade. As such, I’ve drawn only on public sources of information, like news articles and public filings, for this analysis. I do own some Comcast shares which I suppose makes me technically long Accolade, but I have no direct position in Accolade.

[2] Fee for service (FFS) is when providers get paid for each service they provide. More care results in more payment, so under FFS, there is a built-in incentive for providers to perform a lot of expensive care. Contrast with value-based-care (VBC) which, involves some form of flat payment to the provider (per case, or per patient), and means the provider wins by providing less care. In BOTH cases, providers have an information advantage over the patient.

[3] Accolade gets paid on a per-member, per-month, or PMPM basis. I don’t see the exact number in the S-1 but it seems to be at least $5 and possibly closer to $10 PMPM.

[4] Financials. Accolade lost 50 million bucks in fiscal 2020; even ‘Adjusted EBITDA,’ (banker-speak for ‘let’s ignore profit and just focus on cash’) was negative $30 million. What’s the point of all the money-saving care coordination if you have to torch $30 million every year to do it?

One of the big clues in the S-1 is Accolade’s extremely high retention (between 95% and 100% for all 3 reported years). Don’t take them quite at face value though: Accolade typically brings on new customers for 3 year contracts (S-1, pg 32). For a high-growth company, where most customers are less than 3 years old, it makes sense for average churn to be low, but eventually increase as contracts expire. The true life expectancy of a customer relationship is uncertain, but from Accolade’s perspective, the point is that it’s probably very long.

High retention means that money spent on acquiring customers is an expense in the current year, even as the customers themselves will keep paying for many years. Other expenses, like money spent on developing the technology platform, should scale (since the platform is created once, then sold to every customer). To the extent that Accolade has to build a bunch of custom integrations for each new customers—always a risk in healthcare—that will be less true.

More details in the image below. Sorry about the formatting, this was quick and dirty and “for fun.”